This post is the first part of two articles by Martha Farah about neuroscience, ethics, and poverty in relationship to childhood development.

One of the strongest relations in epidemiology is between a person’s socioeconomic status (SES) and their risk of mood and anxiety disorders. In the field of psychometrics, a similarly robust relation is found between SES and cognitive ability as measured by the IQ and other standardized tests. SES predicts a variety of life outcomes, and many of them – like emotional well-being and intelligence – are related to brain function. For this reason, neuroscientists have turned their attention to SES, and to the most materially deprived end of the SES spectrum, poverty.

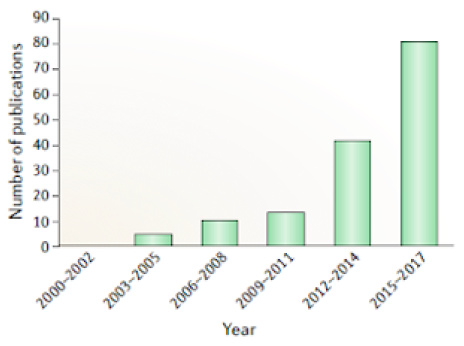

The neuroscience of SES is a young field – even younger than neuroethics! – but it has grown rapidly, as shown in Figure 1. Here, I will focus not on the neuroscience of SES but on the neuroethics of SES. In particular, I will focus on the neuroethics of poverty, which was the topic of a fascinating meeting I just attended at the Medical College of Wisconsin, organized by the neuroethicist Fabrice Jotterand. The meeting was called

“This is Your Brain on Poverty” and brought together people from a mix of disciplines that grapple with poverty: clinicians, scientists, bioethicists, educators, social workers and clergy.

Figure 1. Neuroscience of SES publications.

(Image courtesy of Martha Farah.)

The Neuroscience of Poverty and Neuroethics

One question that arose at the meeting: How should we approach the problem of poverty, and more specifically, can we use neuroscience to approach the problem of poverty without adding further disadvantage to the very people we hope to understand and help? Put bluntly, is the neuroscience of poverty unethical?

Neuroscience itself merely describes facts and tests hypotheses, so on the face of things, it is ethically neutral. For example,

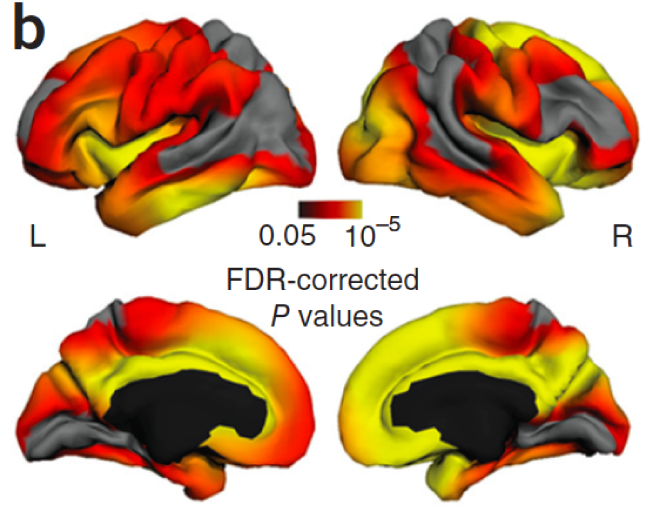

Noble et al. (2015) found that family income was associated with children’s cortical surface area, with wealthier children having greater surface area, particularly in the areas shown in yellow below. However, findings such as these bring to mind images, associations and connotations that may color our attitudes toward the poor, and from there, may even influence our actions toward them. Examples of this follow.

Family income and cortical surface area.

(Image courtesy of Martha Farah.)

Article originally published in: http://www.theneuroethicsblog.com/2019/07/the-neuroethics-of-poverty_2.html

References

- Farah, M. J. (2018). Socioeconomic status and the brain: prospects for neuroscience-informed policy. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, July, 428-438.

- Noble, K.G., Houston, S.M., Brito, N.H., Bartsch, H., Kan, E., Kuperman, J.M., … Sowell, E.R. (2015). Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience, 18(5), 773–8.

The post The Neuroethics of Poverty (Part one) appeared first on Primeros Pasos.